AES is unbreakable. Right?

We are given this python script.

A quick description of what it does: it’s a server that receives messages and replies accordingly. It accepts a set of different commands, if the message starts with specific strings:

get-flag: the server sends the flagget-md5,get-sha1,get-sha256,get-hmac: the server sends the respective hash, computed on the rest of the messageget-time: the server sends the current time- if the message doesn’t start with any recognizable commands, the server replies with

command not found

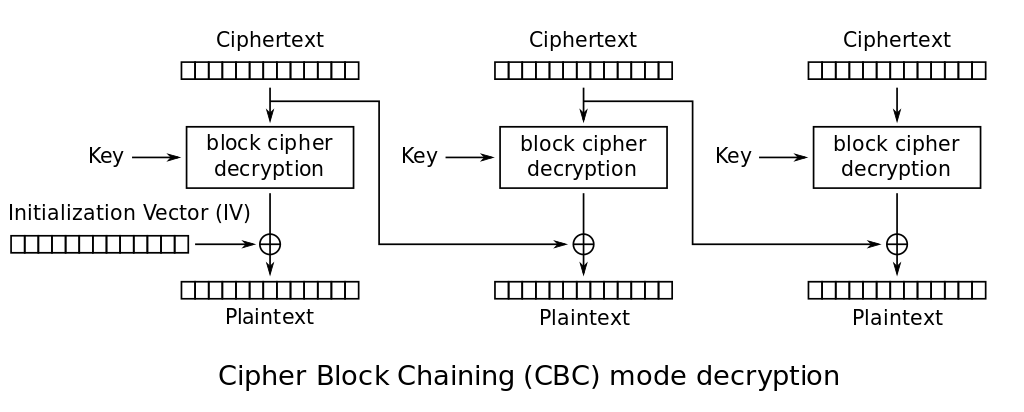

Seems easy, right? We can just send get-flag and solve the challenge, supposedly. Unfortunately, looking at the recv_msg and send_msg functions we can see that the server encrypts every message it sends, and tries to decrypt every message it receives before interpreting them. The server uses AES CBC encryption, with an unknown random key.

Reading the code, we also know:

- that the flag starts with

hitcon{and ends with} - the value of the IV

- the fact that the message starts by sending us an encrypted message of which we know the plaintext (“Welcome!!”)

Furthermore, the implementation for the unpad function seems unusual:

- there is no check if the padding value is under the length of a block

- there is no check if the padding is correct for the whole length of the padding, i.e. if all bytes in the padding length are of the same, correct value

Both checks are needed to comply with the standard PKCS7 padding that is normally used with AES.

So, how can we solve this?

What we can do

Let’s think about what is available to us and what we can otherwise obtain with a little effort.

- We can send forged commands even if we don’t know the key

We have all the necessary ingredients to use the classic “bit flipping attack” on AES CBC.

Basically, we can change how the server will decrypt a ciphertext block by editing the block directly preceding it. This happens because the previous block is XORed with the result of the AES block decryption to produce the plaintext.

Since we know the plaintext for the welcome block, we can just XOR the IV with “Welcome!!” to null the original plaintext out, then XOR it again with our command to replace the original value.

Let’s start by defining some useful functions:

def xor_str(s1, s2):

'''XOR between two strings. The longer one is truncated.'''

return ''.join(chr(ord(x) ^ ord(y)) for x, y in zip(s1, s2))

def flipiv(oldplain, newplain, iv):

'''Modifies an IV to produce the desired new plaintext in the following block'''

flipmask = xor_str(oldplain, newplain)

return xor_str(iv, flipmask)We should also retrieve and keep the encrypted welcome message as base for the bit flipping operations.

Note: we are going to use the pwntools libraries to communicate with the server.

HOST = '52.193.157.19'

PORT = 9999

welcomeplain = pad('Welcome!!')

p = remote(HOST, PORT)

solve_proof(p)

# get welcome

welcome = p.recvline(keepends=False)

print 'Welcome:', welcome

welcome_dec = base64.b64decode(welcome)

welcomeblocks = blockify(welcome_dec, 16)- Since we can now send any command, we can obtain the encrypted flag by sending the

get-flagcommand

# get encrypted flag

payload = flipiv(welcomeplain, 'get-flag'.ljust(16, '\x01'), welcomeblocks[0])

payload += welcomeblocks[1]

p.sendline(base64.b64encode(payload))

flag = p.recvline(keepends=False)

print 'Flag:', flag- We can also get a hash (any from the set) of the decrypted message from an index onwards

From the 7th character for the MD5 hash, from the 8th for the SHA1 hash, etc.

To invoke the command we can perform the same bit flipping operation we did for the get-flag step, but this time using get-md5, get-sha1 or one of the others.

- We can control the value of the last byte of the message, and therefore the size of the message that will be truncated away

We can append the IV and the welcome block to any of the messages we send if we want.

Since we know the plaintext for the welcome block, we can edit the IV block as we did before to control how the last block will be decrypted. If we modify the last byte of the last block, we can control how much of the message will be unpadded away, and cut it at any place we want, up to 256 characters.

Ideas and attacks

How can we use all this to reveal the flag?

The fact that we can control how much of the message will be removed after decryption made me wonder if an approach in some way inspired to the padding oracle attack is feasible. We don’t have a padding oracle in this case, but can we still somehow fashion a way to reduce the search space of the plaintext from 256^16 possibilities (all the characters at the same time) to a much more doable 256*16 (i.e. guessing one character at a time)?

The answer is yes, and there are actually multiple ways to do so. The first one that came to my mind, and the one that I used in this challenge, is the following:

-

Since we know the first 7 bytes of the flag (

'hitcon{') we can replace them withget-md5to receive the encrypted MD5 hash of the rest of the flag, the part following the first curly brace. -

By replacing the beginning of the flag with

get-md5and exploiting the flawedunpadmethod, we can obtain the encrypted MD5 hash not only of the whole flag, but also of the truncation up to an index we can specify.

For instance we can get the encrypted MD5 hash for the first letter of the flag, then the one for the first two letters, then for three, and so on. -

We can compute MD5 hashes locally.

We can e.g. compute hashes of every 256 single ASCII character if needed. If we knew the first letter of the flag, we could also compute all the hashes of that character followed by each of the possible 256 ASCII characters, and so on. -

We can send encrypted MD5 hashes back to the server, which will decrypt it. We can also edit them in the same way as we did with the welcome message: if we can correctly guess the plaintext value of the hash, we can null it out and replace it with a value of our choosing, like, for example, one of the commands.

-

Finally, the actual attack idea: let’s say we get the encrypted MD5 hash for the flag, truncated after the first letter. We can then locally compute the MD5 hash for every possible character in the 256 ASCII range. Next we send back the original hash for the truncated flag, but nulled out with one of the guessed hashes and replaced with a command (let’s say

get-time). If the hashes is correctly guessed (i.e. it’s the hash for the string containing the same characters as the flag), then the command will be correctly executed and we will receive a new, unknown ciphertext. If the guessed hash is wrong, we will instead receive the ciphertext forcommand not found, which is fixed and easily known.

Once we find the correct value for the first letter we can move to the next and repeat the same procedure, but this time we will compute the hash of the part of the flag we already know concatenated with the new guessed character.

We can repeat this for all the indexes of the flag, up to the end, and discover the whole flag.

With the procedure as decribed, we can find a single character in at most 256 guesses, then add it to the part to the flag that we know and move on to the next character. We can therefore guess one character at a time without much effort!

In practice we can say that command not found is an oracle, which can tell us if the first 7 bytes were correctly decrypted as a command or not. We can use this to know which MD5 hash is correct (and thus which original string).

Someone could point out that the oracle is slightly inaccurate, since the wrong MD5 hash could decrypt as a different command than get-time. This is very, very unlikely though, since we test only 256 hashes per character and the chance of decrypting as a different command is in the order of 1/256^7 (get-md5 is 7 characters long).

Putting everything together

All this long exposition can be summarized with the exploit which you can find at the end of this writeup.

When running the script the flag is, slowly but surely, correctly decrypted character by character. The final result is hitcon{Paddin9_15_ve3y_h4rd__!!}.

from pwn import *

import base64, random, string

from Crypto.Hash import MD5, SHA256

def pad(msg):

pad_length = 16-len(msg)%16

return msg+chr(pad_length)*pad_length

def unpad(msg):

return msg[:-ord(msg[-1])]

def xor_str(s1, s2):

'''XOR between two strings. The longer one is truncated.'''

return ''.join(chr(ord(x) ^ ord(y)) for x, y in zip(s1, s2))

def blockify(text, blocklen):

'''Splits the text as a list of blocklen-long strings'''

return [text[i:i+blocklen] for i in xrange(0, len(text), blocklen)]

def flipiv(oldplain, newplain, iv):

'''Modifies an IV to produce the desired new plaintext in the following block'''

flipmask = xor_str(oldplain, newplain)

return xor_str(iv, flipmask)

def solve_proof(p):

instructions = p.recvline().strip()

suffix = instructions[12:28]

print suffix

digest = instructions[-64:]

print digest

prefix = ''.join(random.choice(string.ascii_letters+string.digits) for _ in xrange(4))

newdigest = SHA256.new(prefix + suffix).hexdigest()

while newdigest != digest:

prefix = ''.join(random.choice(string.ascii_letters+string.digits) for _ in xrange(4))

newdigest = SHA256.new(prefix + suffix).hexdigest()

print 'POW:', prefix

p.sendline(prefix)

p.recvline()

HOST = '52.193.157.19'

PORT = 9999

welcomeplain = pad('Welcome!!')

p = remote(HOST, PORT)

solve_proof(p)

# get welcome

welcome = p.recvline(keepends=False)

print 'Welcome:', welcome

welcome_dec = base64.b64decode(welcome)

welcomeblocks = blockify(welcome_dec, 16)

# get command-not-found

p.sendline(welcome)

notfound = p.recvline(keepends=False)

print 'Command not found:', notfound

# get encrypted flag

payload = flipiv(welcomeplain, 'get-flag'.ljust(16, '\x01'), welcomeblocks[0])

payload += welcomeblocks[1]

p.sendline(base64.b64encode(payload))

flag = p.recvline(keepends=False)

print 'Flag:', flag

flag_dec = base64.b64decode(flag)

flagblocks = blockify(flag_dec, 16)

flaglen = len(flag_dec) - 16

known_flag = ''

def getmd5enc(i):

'''Returns the md5 hash of the flag cut at index i, encrypted with AES and base64 encoded'''

# replace beginning of flag with 'get-md5'

payload = flipiv('hitcon{'.ljust(16, '\x00'), 'get-md5'.ljust(16, '\x00'), flagblocks[0])

payload += ''.join(flagblocks[1:])

# add a block where we control the last byte, to unpad at the correct length ('hitcon{' + i characters)

payload += flipiv(welcomeplain, 'A'*15 + chr(16 + 16 + flaglen - 7 - 1 - i), welcomeblocks[0])

payload += welcomeblocks[1]

p.sendline(base64.b64encode(payload))

md5b64 = p.recvline(keepends=False)

return md5b64

for i in range(flaglen - 7):

print '-- Character no. {} --'.format(i)

# get md5 ciphertext for the flag up to index i

newmd5 = getmd5enc(i)

md5blocks = blockify(base64.b64decode(newmd5), 16)

# try all possible characters for that index

for guess in range(256):

# locally compute md5 hash

guess_md5 = MD5.new(known_flag + chr(guess)).digest()

# try to null out the md5 plaintext and execute a command

payload = flipiv(guess_md5, 'get-time'.ljust(16, '\x01'), md5blocks[0])

payload += md5blocks[1]

payload += md5blocks[2] # padding block

p.sendline(base64.b64encode(payload))

res = p.recvline(keepends=False)

# if we receive the block for 'command not found', the hash was wrong

if res == notfound:

print 'Guess {} is wrong.'.format(guess)

# otherwise we correctly guessed the hash and the command was executed

else:

print 'Found!'

known_flag += chr(guess)

print 'Flag so far:', known_flag

break

print 'hitcon{' + known_flagLet us know what you think of this article on twitter @towerofhanoi or leave a comment below!